Fashion, historically, has always been exclusive. For decades—even centuries—if you didn’t have the right height, weight, or racial background, you were scoffed at, ignored, and ultimately overlooked, regardless of how much talent you possessed. So many of these barriers have since been broken, with so many heroes rightfully receiving recognition for the doors they broke down. But yet and still, there are groundbreaking figures who are either hidden in the shadows, only receiving small mentions here and there, or are completely left by the wayside, with only the most dedicated pupils of black and fashion history alike even hearing their names. So, in honor of Juneteenth, I’d like to shine a beautiful spotlight on five historic black figures in the fashion world who deserve their rightful seat at the trailblazing table.

Ophelia DeVore

Emma Ophelia DeVore was one of ten children born to John and Mary (Strother) DeVore in the southern city of Edgefield, South Carolina. She was of mixed German, African, and Cherokee ancestry and grew up comfortably until she moved to New York City at the age of fourteen for a better education.

Originally wanting to be a movie star, DeVore settled for modeling after her parents’ strong disapproval of the former. Enrolling herself in the Vogue School of Fashion Modelling, she eventually became the first black woman (unbeknownst to the school) to graduate. After a brief modeling career, DeVore took her experience and the knowledge she gained from Vogue and opened The Grace Del Marco Agency, a modeling agency focused on advancing non-white models in the industry. Soon after, she created her own charm school, the Ophelia DeVore School of Charm, which went on to mold many future stars, such as Diahann Carroll, Cicely Tyson, Richard Roundtree, and modeling pioneer Helen Williams, to name a few.

Both businesses eventually closed in 2005, but the decades of work that Ophelia DeVore put into her brand and its many apprentices can never be diminished. You can read DeVore’s incredible story in her own words here.

Elizabeth Keckley

Elizabeth Keckley was born in Dinwiddie, Virginia, in February 1818, to an enslaved woman and her slave master. Her clothes-making skills, which she picked up from her mother, would become her ticket to a better life. After surviving a harsh childhood and an even more severe young adulthood, Keckley finally purchased her and her son’s freedom in 1855.

Keckley eventually found her way to Washington and, using the tricks she picked up during her brutal enslavement, made dresses for the women of D.C. until she struck gold, earning the wife of Confederate General Robert E. Lee as a customer. From there, her business rapidly grew until she struck gold a second time, now counting Mary Todd Lincoln (the wife of Abraham Lincoln) amongst her clientele. Keckley and the Lincolns got along famously, with the former spending many private moments at the White House and being treated with the utmost respect. She even accompanied the First Couple on their visit to Richmond, Virginia, shortly after the Civil War (a war in which Keckley lost her son) ended.

Perhaps her most important Civil Rights work is her establishment of the Ladies’ Freedmen and Soldier’s Relief Association, which helped newly freed enslaved persons create a foundation for their new lives until they could earn a living on their own. Later in life, she wrote an autobiography, which is now used to give insight into the plight of the enslaved. You can read Keckley’s grueling but remarkable journey here.

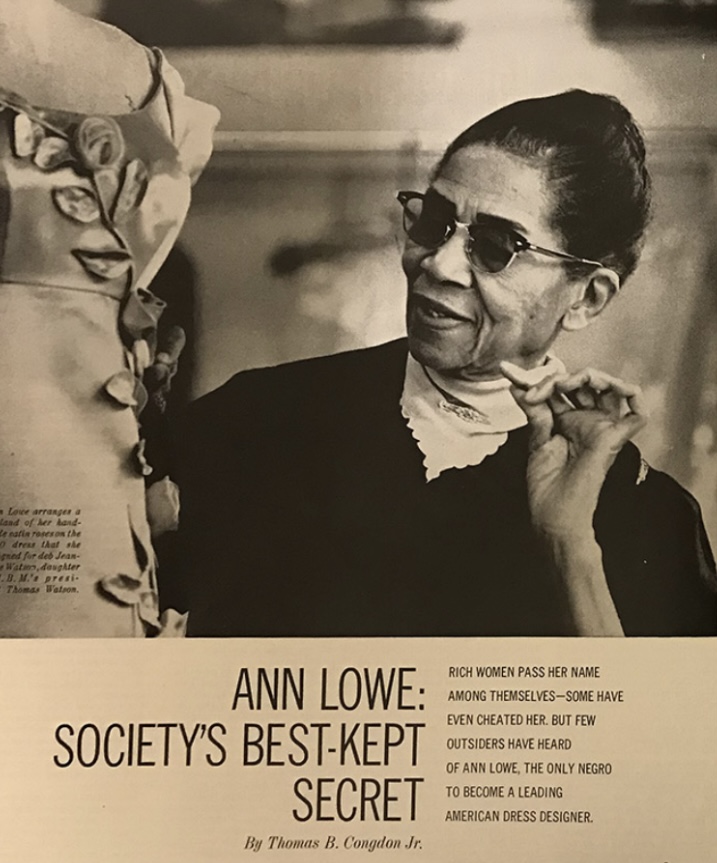

Ann Lowe

Born in Clayton, Alabama, sometime around 1898 (sources vary) to Jack and Jane (also called Janie or Janine) Lowe, Ann Cole Lowe learned to sew at the age of five from her mother and grandmother, who sewed elegant dresses for the elite families of Alabama. After her mother’s sudden passing, Lowe, then somewhere in her mid-teens, continued her mother’s final projects, earning her own stripes within the state.

Lowe eventually found her way to New York and enrolled at the S.T. Taylor School of Design. Despite being forced to segregate from her classmates, she completed her curriculum in about half the expected time. After moving her business around the country several times, she permanently settled in New York in 1928. After suffering some serious financial loss, piled with the onset of the Great Depression, Lowe sought work at other fashion houses of the day, where she made some important connections with wealthy clients who were on the Social Registry. This would lead to her eventual Ebony Magazine quote, “I love my clothes and I’m particular about who wears them. I am not interested in sewing for cafe society or social climbers. I do not cater to Mary and Sue. I sew for the families of the Social Register.”

After nearly two more decades of building her brand in the fashion circuit, Lowe was chosen by Janet Auchincloss to be the bridal dressmaker for her daughter, Jacqueline Bouvier, and her bridesmaids. Despite a terrible flood destroying the main dress and most of the bridesmaids 10 days before the big day; Lowe and her team toiled through and recreated each one just in time. Unfortunately, when the new Mrs. Kennedy was asked who designed her wedding dress, she merely replied that it was a “colored” woman. Lowe wouldn’t get public credit for the dress until the mid-1960s after Mrs. Kennedy left the White House.

Lowe continued, amidst many troubles, to design for the elite of New York until her retirement in 1972. Many of her creations are currently on display at the Costume Institute at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and a few more are showcased at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, where you can read a more detailed account of her tumultuous odyssey here.

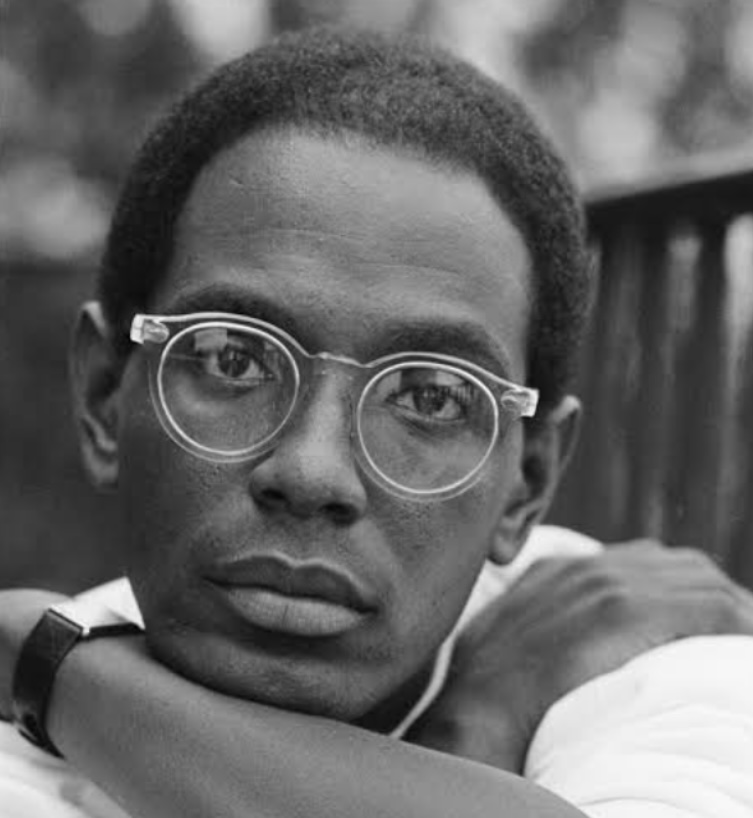

Willi Smith

Not to be confused with Hollywood actor Will Smith (though they were both from Philadelphia), Willi Smith came into this world during a leap year on February 29, 1948. As a child, Smith adored sketching, and he had a supportive mother—who told him he was born to be an artist or designer—and a grandmother who later encouraged him to follow his dreams of design.

After attending multiple colleges (studying commercial art, then fashion illustration, and finally attending Parsons The New School For Design), Smith got an internship with couturier Arnold Scaasi through his grandmother. He then tried his own hand at designing, eventually becoming lead designer for junior sportswear at Digits, where he would be nominated for the Coty American Fashion Critics’ Award for two years straight, finally winning the second time. Soon after, Smith resigned from Digits and started his own label, Willi Smith Designs Inc., with his friend, modeling pioneer Bethann Hardison, and his sister, Toukie Smith. However, the business soon crumbled since none of them really knew how to run the business side of fashion. Not to be deterred, Smith kept on. After creating a successful collection in Bombay, India (now called Mumbai), Smith founded WilliWear Ltd. with Laurie Mallet, a friend he made while working at Digits.

WilliWear immediately stood out by selling natural fabrics at an affordable price. The garments at his shows were clearly inspired by Southeast Asian culture, while his ready-to-wear had a flair for sportswear. The company soared, reaching a peak of $25 million in sales in 1986 before Smith’s sudden death from AIDS in 1987. Due to his accomplishments, Willi Smith is still regarded as one of fashion’s most successful African American designers. While his business may no longer be in operation (officially closing its doors in 1990), his work opened the door for many trends we see today, like affordable quality and athleisure.

Patrick Kelly

First opening his eyes on September 24, 1954, Patrick Kelly would take the fashion world by storm in his short thirty-five years of life. Born and raised in Vicksburg, Mississippi, it’s said that a very young Kelly was looking through some fashion magazines his grandmother brought home one day. When he asked her why there were no black models and received an unsatisfactory answer, he decided he wanted to change that.

Picking up sewing in high school, Kelly started designing in Atlanta, Georgia, to which he received mostly positive reviews. Setting his sights higher, he moved to New York City and enrolled on a scholarship at Parsons School of Design. The scholarship was rescinded once the school realized he was a black man (instead of an Irish one, as they had presumed). Frustrated with the blatant discrimination of the fashion world, Kelly confided in his friend, African American model Pat Cleveland, who suggested that he try his luck in Paris before getting him a ticket to go.

Once in the City of Love, Kelly started working at Le Palais (The Palace), which is said to be the French equivalent of Studio 54, where he was tasked with designing the costumes. He was featured in Elle France and struck a deal with Warnaco, a former textile company, in 1987, where his designs would finally be sold globally. The next year, he became the first American to be admitted to the Chambre syndicale du prêt-à-porter des couturiers et des créateurs de mode (today called the Fédération de la Haute Couture et de la Mode), putting his brand on the same footing as YSL, Dior, Chanel, etc. Kelly’s jubilant but sober spirit was reflected in his brand, making him stand out with things like the heart he spray painted before every runway show or his own positive spin on the golliwog, using it as his brand’s logo.

Kelly was a proud member of the LGBT community and passed away due to complications with AIDS on January 1, 1990. Many of his creations are held between the Philadelphia Museum of Art and his alma mater, Jackson State University, where you can still see them.

Countless innovative spirits have made the fashion industry what it is today. And, realistically, we probably can’t track and thank each and every one. But the more we catch, the better. Instead of singing the same handful of names, let’s expand our praises to the lesser-known but equally important events, places, and people who have made it easier for us to express ourselves as we now can.

Which of these stories was your favorite? Did you learn anything new? Let us know!

XOXO,

Your Fashion Bestie

1 Comment

Love it. Thanks for the knowledge Learned things I didn’t know